I love you – the Chinese way

Are you aware that for the Chinese, it’s double Valentine’s this year?

CNY ends today, the 15th of the first month. This day is called 元宵节 (Yuánxiāo Jié) or 灯节 (Dēng Jié – Lantern Festival). It is also regarded as the traditional Chinese Valentine’s Day. Girls in the past were not allowed to get out of the house like we do today, but it is said that on this day, they could go to the Lantern Festival, where they had the opportunity to meet young men. It happens that for the year 2014, the Lantern Festival falls on February 14th. As is to be expected, the number of couples getting married this day is much higher than other days. (See report here.)

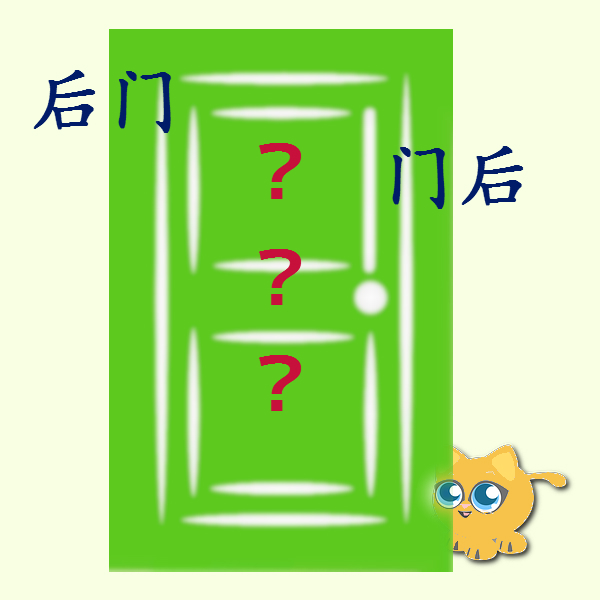

The topic today is not about the Lantern Festival though. Rather, I would like to talk about the concept of love in Chinese culture. I’m often asked by foreigners what is ‘I love you’ in Mandarin. It’s very short and sweet – “我爱你” (wǒ ài nǐ). But the bigger question is, I think, how natural is this expression to Chinese ears?

If we look at Chinese love songs, we can find many ‘I love you’ phrases. Here are some famous songs.

《小薇》(Xiǎowēi)

《约定》(Yuēdìng)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6tocDT-qqY

At the end of the song, there is the promise “我会好好地爱你 傻傻爱你” (Wǒ huì hǎohao de ài nǐ, shǎshǎ ài nǐ – I will love you well, I will love you like a fool)

《你怎么舍得我难过》(Nǐ zěnme shěde wǒ nánguò)

《爱你爱你》(Ài nǐ ài nǐ)

Songs are supposed to reflect people’s emotions, so if you hear it often in songs, you should also hear it from real people, right? Turns out it might not be true. Traditional Chinese people are not used to expressing themselves candidly. “含蓄” (hánxù – being implicit) is considered a virtue of sorts, and people in general prefer to beat around the bush and be euphemistic. Displaying everything in its totality, especially emotions, is not quite in sync with the Chinese psyche. “Wǒ ài nǐ” is ultimately a Western concept. Lovers hardly use it. It is even less common to hear it among family members. To openly and overly express one’s feelings can be seen as “肉麻” (ròumá – nauseating).

爱 (ài)、喜欢 (xǐhuan)、疼 (téng) to love, to like or to dote

It is perhaps a good idea to be acquainted with other terms of affection. Apart from “爱” (ài), two other terms come to mind – “喜欢” (xǐhuan) and “疼” (téng). To begin with, “爱” (ài) is a huge word, and to my mind, not a term to be used easily. Someone who easily rattles out words of deep affection might also be viewed as unreliable. Even if one wanted to convey one’s adoration, it is more common to say “我喜欢你” (Wǒ xǐhuan nǐ – I like you).

However, the most common term is probably “疼” (téng), which would translate to ‘to dote on, to be very fond of’. It might not sound exactly like the kind of love Westerners can immediately understand. In general, this is a feeling you might have to someone younger or someone you want to take care of. So parents ‘téng’ their children, teachers ‘téng’ their students, boyfriends ‘téng’ their girlfriends. It is also a common view that if a woman finds a man who ‘téng’s’ her (pardon the weird English!), then she is on the right track to happiness. This mindset, however, is changing, I believe. Now that women are more on par with men, some do not want to be loved this way. When I was a teenager, I had a classmate who told me she didn’t want to have a husband who would ‘téng’ her. At the time, I was baffled to hear this.

《爱你在心口难开》(Ài nǐ zài xīn kǒu nán kāi)

Rather than “wǒ ài nǐ”, it sounds more natural to say “我关心你” (Wǒ guānxīn nǐ – I care about you) or “我担心你” (Wǒ dānxīn nǐ – I worry about you). These expressions however are also common among friends, so it might be quite ambiguous.

If you have to show in certainty your affection, these are some other expressions used.

Wǒ duì nǐ shì zhēnxīn de

我对你是真心的。

My feelings to you are true.

Nǐ zhīdao wǒ zuì téng nǐ de

你知道我最疼你的。

You know I dote on you most.

Wǒ zàihu nǐ

我在乎你。

I care about you.

Wǒ de xīnyì nǐ hái bù dǒng ma

我的心意你还不懂吗?

Don’t you know my heart by now?

Wǒ hěn xiǎng nǐ

我很想你。

I miss you.

Wǒ xīnli zhǐ yǒu nǐ

我心里只有你。

You are the only one in my heart.

Wǒ zhǐ duì nǐ hǎo

我只对你好。

I am affectionate only to you. (literally, I am kind to no others except you.)

Nǐ duì wǒ zuì hǎo le

你对我最好了。

You love me most. (literally, you treat me best.)

Nǐ chīcù le ma

你吃醋了吗?

Are you jealous?

Wǒ yào yíbèizi bǎohù/ zhàogu nǐ

我要一辈子保护/照顾你。

I will protect you my whole life.

Xià bèizi wǒ yě yào gēn nǐ zài yìqǐ

下辈子我也要跟你在一起。

I want to be with you in my next life too.

Having said so much, it does seem that Chinese people are getting more liberal in self-expression. I have been surprised on quite a few occasions recently to hear characters in period dramas say “你爱我吗 (Nǐ ài wǒ ma – do you love me?) and “我很爱他” (Wǒ hěn ài tā – I love him very much). As a modern person who grew up in Singapore and being fairly in touch with Western culture, I still blush when I hear such expressions, especially from ancient people! Perhaps my awkwardness only reveals my age. I can’t help wondering if the younger generation finds it a breeze to say I love you in Chinese. In Singapore, we hardly hear anybody say it in Chinese, but in English, it’s not that uncommon. By the way, if my husband were to say it to me, I’d probably put my hand on his forehead to check if he was having a fever.

How about between parents and children? According to this article, there was a recent experiment whereby young people called their parents to say ‘wǒ ài nǐ’. While some parents were happy to hear that and responded gamely, most were taken aback. They either did not quite know what to say or retorted with questions like ‘Are you drunk?’, or ‘Are you in need of money?’. This is the video, which is heart-warming but also at the same time hilarious as I can definitely relate to the stunned responses. *

Before I end off, I would like to share another observation. It is something personal but I believe other Chinese people raised in English environments probably have similar sentiments. While I find it almost impossible to say “wǒ ài nǐ”, somehow it is easy to end emails with ‘love’. At times, I even can’t resist saying ‘lots of love’. It seems that when the English mode button is switched on, I take on a slightly different personality. Verbalising it is still unthinkable, but writing it does not seem like mission impossible – the English language seems to make me a little more candid.

Does the Chinese way of loving surprise you? Do share your thoughts and experiences!

Until next time. Meanwhile, Happy Valentine’s, and also, 元宵节快乐 (Yuánxiāo Jié kuàilè – Happy Yuanxiao)!

*The original video I embedded has been taken down, so this is another video, but essentially doing the same experiment. (2015 Mar 28)

If you’ve enjoyed this, don’t forget to hit one of the sharing buttons below, and do join me on Google+/ Facebook/ Youtube/ Twitter/ Pinterest !